Malay Film Productions & Cathay-Keris Studio (1943 - 1973)

During the 1950s and 1960s, Singapore experienced a wave of locally-produced Malay films from the Malay Film Productions and Cathay-Keris Studio. In their hey-days, these studios produced and distributed countless Malay-language films. Some of these films were box-office hits which won film awards. These studios faced a decline with the arrival of television. The two studios ceased operations by the late 1960s and early 1970s, marking the end of what was regarded as the golden age of Malay films.[1]

Malay Film Productions (1943 - 1967)

Origin

Formed in 1943, the Malay Film Productions was a subsidiary of Shaw Organisation which was run by the Shaw Brothers, Mr Runme Shaw and Mr Run Run Shaw.[2] The film studio was located at Jalan Ampas, off Balestier Road.[3] The studio was equipped with the most up-to-date sound recording equipment and motion picture cameras from America.[4] The studio solely produced Malay-language films to meet the growing demand. The studio established a monopoly over the Malay film market and the local movie scene by 1948.[5]

Film productions

Malay Film Productions released its first film in 1947, titled Singapura Diwaktu Malam (Nighttime in Singapore).[6] By 1957, the studio turned out more than 100 films, some of which won awards.[7] For instance, the film Hang Tuah (1956) won the “The Best Music” in the 3rd Asian Film Festival and Madu Tiga (Three Rivals; 1964) won the “Best Comedy” award in the 11th Asian Film Festival.[8] Despite these successes, the studio was constantly beset by labour unrest and competition from Cathay-Keris Studio.

1957 labour strike (Singapore Malay Artists’ Union)

On 27 February 1957, Malay film stars and technicians from the Malay Film Productions submitted a list of demands through the Singapore Malay Artists’ Union. This list was directed to the management of Shaw Brothers asking for higher wages and bigger bonuses. The list included:[9]

- An agreed salary scale for the various categories of studio employees.

- Bigger bonuses for each completed picture.

- Prompt overtime payment

- A half-holiday on Saturdays and Sundays off.

The demands were made after considering the existing salary of both leading and supporting actors and actresses. As of 1957, the monthly salaries for employees were as such:[10]

| Monthly salary | Bonus | |

|---|---|---|

| Lead actor | $250 | $400 - S$500 |

| Lead actress | $150 | $400 - S$500 |

| Supporting actor/ actress | $80 - S$120 | $150 |

On 28 February 1957, the Shaw Brothers management reported that they did not receive any news of such demands.[11] The matter escalated in March when Shaw Brothers dismissed five employees of Malay Film Productions who were members of the Union. The union threatened to call a strike if the workers were not reinstated by March 16.[12] Shaw Brothers then warned the Union that any members would be sacked if they participated in the strike.[13]

After the Union failed to secure Tengku Abdul Rahman’s intervention in the dispute, they held a concert, called “Malam Suka Duka” (Happy and Unhappy Night) to raise funds for the strike.[14] Led by the Union President, P. Ramlee, 23 actors and actresses took part in the two-day show at the Happy World Stadium.[15] On 16 March 1957, 120 MFP employees went on strike at the Jalan Ampas studio. Members of the Union picketed the studio with strike banners, calling for the reinstatement of the dismissed employees.[16]

Following the strike, The Shaw Brothers management revealed that the company had been incurring significant financial losses due to rising salaries and production costs.[17] While talks happened between the striking employees and the management, no conclusive decision was reached for a few weeks.[18]

On 7 April, the Union agreed to call off the 23-day strike after the Shaw Brothers promised to reinstate the five dismissed members.[19] On 18 April, work resumed at the Malay Film Productions.[20]

1964 labour strike (Industrial Workers’ Union of Singapore)

On 26 November 1964, the Industrial Workers’ Union of Singapore gave the management of Shaw Brothers a one-week ultimatum. The management was required to settle the wage claims of 70 technicians under its employment or face strike action.[21] On 4 December, around 75 workers went on a strike against the company.[22] Organisations sympathetic to their cause provided help in the form of food and money.[23]

The 55-day strike was called off on 29 January 1965 after the Union reached an agreement with the management.[24]

Closure

Throughout the 1960s, Shaw Organisation and the Malay Film Productions experienced a decline in film productions. In 1960, 9 films were completed while 1961 and 1962 saw the company completing 8 films in each year. The numbers fell in 1963 and 1964 as only 6 and 5 films were completed respectively. Citing that it was uneconomical to continue operations and the increasing competition with television, the management decided to close down its studios at Jalan Ampas. Shaw Brothers issued a two-month dismissal notice to the 105 employees of Malay Film Productions.[25]

On 28 October 1967, it was reported Malay Film Productions had gone into voluntary liquidation and chartered accountants had been appointed to wind up its affairs.[26]

Cathay-Keris Studio (1951 - 1973)

Origin

Cathay-Keris Studio was a joint partnership between Dato’ Loke Wan Tho and Mr Ho Ah Loke.[27] A direct challenge to Shaw’s Malay Film Productions, Cathay-Keris Studio ended the monopoly Shaw had over Malay cinema. Cathay-Keris began filming their first production in 1951. In 1953, Cathay-Keris released its first film, “Buloh Perindoh”. The film was marketed as “the first Malay picture in Gevacolour”.[28]

Recognising that it lacked Shaw’s expertise in film production, Cathay-Keris approached employees from Malay Film Productions with financially attractive contracts.[29] According to S Kadarisman, a former actor at Malay Film Productions, this move caused the 1957 labour unrest. Cathay-Keris offered a substantial amount to any employees that changed film studios.[30]

Film productions

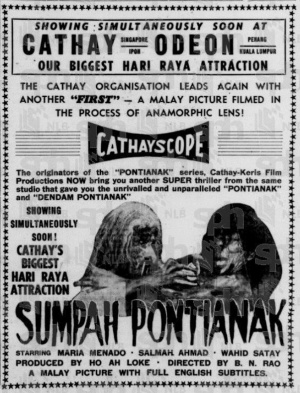

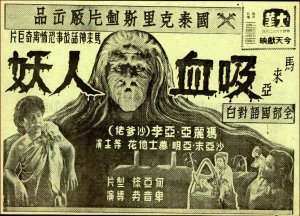

Cathay-Keris was recognised for its horror films, starting from the 1957 film ‘Pontianak’. The film was so successful that it was dubbed into Chinese and re-released for its Chinese audience. Three more sequels were made after Pontianak’s success in 1958, 1963 and 1964. These sequels continued to attract a large audience.[31]

In 1958, Cathay-Keris Studio released another horror movie, Sumpah Orang Minyak (The Curse of the Oily Man) which was both a crowd pleaser and a high box-office earner.[32]

1961 labour strike (Singapore General Employees’ Union)

On 12 December 1961, more than 100 Cathay-Keris employees ceased work at the studio. The employees, who were members of the Singapore General Employees’ Union, stopped work after negotiations on wage claims broke down with the management.[33]

The strike ended after seven days following an agreement between the Union and the management. According to Mr Dominic Puthucheary, Vice President of the Singapore General Employees’ Union, the agreement promised the following:[34]

- A wage increase of S$15 a month

- Two weeks of annual leave

- One month’s bonus

- Free medical treatment

- 10% “incentive bonus” of profits earned from the picture

Cathay-Keris 10-year Anniversary (1962)

Cathay-Keris celebrated its 10-year anniversary with newspaper supplements in both The Straits Times and Berita Harian. In The Straits Times, the 6-page long supplement recorded Cathay-Keris successes as the “pioneer” of a brand new industry.[35] It noted that Cathay-Keris Studio has hosted more than 12,000 visitors in 1961 as a result of its “open door” policy.[36]

Similarly, a 10-year anniversary supplement in the Berita Harian documented Cathay’s box office successes and its film productions.[37] The 4-page supplement noted that 30% of Cathay-Keris films’ audience was not Malay which was an indicator of the studio’s wide-reach.[38]

Closure

Like Malay Film Productions, Cathay-Keris faced a decline due to the rising costs of production and the popularity of television. The studio experienced diminishing box-office returns due to a decreasing number of cinema patrons.[39] Cathay-Keris Studio’s last film, Hati Batu, was released in 1973.[40]

References / Citations

- ↑ Loh, Khim. “Kachang puteh to popcorn: a history of Singapore film”. Mediacorp TV12. 1999. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from YouTube.

- ↑ Nan Hall. “Showman Shaw declines to share secrets, says hard work and luck help”. The Straits Times. April 20, 1958. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “New film studio in Singapore planned”. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. June 18, 1941. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Roy Ferroa. “Making films in S’pore”. The Singapore Free Press. March 9, 1948. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Page 9 Advertisements Column 1”. The Straits Times. February 7, 1948. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “S’pore makes more Malay movies”. Malaya Tribune. December 23, 1947. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Nan Hall. “Showman Shaw declines to share secrets, says hard work and luck help”. The Straits Times. April 20, 1958. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “4 ‘Oscars’ for Malaya in Festival”. The Straits Times. June 17, 1956. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Malay film stars want more pay”. The Straits Times. February 27, 1957. Accesssed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Malay film stars want more pay”. The Straits Times. February 27, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Film stars’ demands - ‘no news’”. The Straits Times. February 28, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Shaw Brothers won’t talk”. The Straits Times. March 8, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Tengku meets film men”. The Straits Times. March 14, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Tengku meets film men”. The Straits Times. March 14, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Concert planned to raise strike fund”. The Straits Times. March 15, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Actors on strike today”. The Straits Times. March 16, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Strikers are told: Teamwork alone can save film industry”. The Straits Times. March 17, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ "Stars’ plea to Mentris”. The Straits Times. March 30, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Film workers’ strike over”. The Straits Times. April 8, 1957. Accessed 5 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Striking stars work again”. The Straits Times. April 18, 1957. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Ultimatum by union to film company”. The Straits Times. November 26, 1964. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Film strike still on”. The Straits Times. January 13, 1965. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “75 pemogok dapat bantuan”. Berita Harian. December 31, 1964. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “55-day film strike off”. The Straits Times. January 29, 1965. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “A do-it-yourself offer to sacked stars”. The Straits Times. May 8, 1965. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Film company goes into liquidation”. The Straits Times. October 28, 1967. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “New film studio is biggest yet”. The Straits Times. November 25, 1951. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Page 8 Advertisements Column 1”. The Straits Times. November 19, 1953. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Loh, Khim. “Kachang puteh to popcorn: a history of Singapore film”. Mediacorp TV12. 1999. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from YouTube.

- ↑ S. Kadarisman. “Communities of Singapore (Part 3)”. National Archives of Singapore. May 6, 1986. Accessed 2 August 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Loh, Khim. “Kachang puteh to popcorn: a history of Singapore film”. Mediacorp TV12. 1999. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from YouTube.

- ↑ Loh, Khim. “Kachang puteh to popcorn: a history of Singapore film”. Mediacorp TV12. 1999. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from YouTube.

- ↑ “Cathay-Keris film studio paralysed by strike”. The Straits Times. December 12, 1961. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cathay staff back after seven-day strike”. The Straits Times. December 19, 1961. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cathay-Keris A true pioneer industry - and not a cent in aid”. The Straits Times. January 30, 1962. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Every year thousands of visitors make a tour of studios”. The Straits Times. January 30, 1962. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Senarai kemajuan Cathay”. Berita Harian. January 30, 1962. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “30 peratus penonton2 bukan Melayu”. Berita Harian. January 20, 1962. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Loh, Khim. “Kachang puteh to popcorn: a history of Singapore film”. Mediacorp TV12. 1999. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from YouTube.

- ↑ “Hati Batu filem terakhir M. Amin dgn Cathay”. Berita Harian. September 2, 1973. Accessed 1 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.