University of Singapore "Cracker Wars" (1964 & 1965)

During the 1960s, three hostels accommodating students from the University of Singapore engaged in annual 'Cracker Wars’ fueled by inter-hall rivalry.[1] While this tradition rarely made headlines, the 1964 and 1965 ‘Cracker Wars’ between the boys from Raffles Hall and Dunearn Road Hostel against the all-girls Eusoff College captured the public’s attention as they had occurred during a nationwide firecracker ban. The "Cracker Wars" occurred at around the same period as the Eusoff College panty raids involving Raffles Hall.

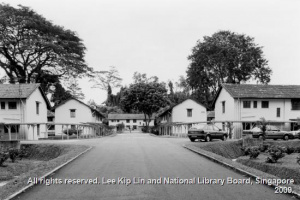

At the time, Raffles Hall and Eusoff College were all-boys and all-girls hostels respectively.[2] Dunearn Road Hostel was initially a co-ed hostel but at the time of the incidents, it had been temporarily converted into an all-male hostel due to a declining student population.

1964 - 1965 New Year’s Eve "Cracker War"

Details of incident

On 31 December 1964, Raffles Hall hostelites launched a New Year’s Eve ‘Cracker War’ on Eusoff College. The war lasted into the early hours of the New Year and was remembered for the extensive physical damage to the hostel and personal property. Lighted crackers were thrown into the girls’ rooms, windows and doors were broken and several bedsheets and dresses were burnt.[3]

Responses (Junior Common Room Committees & police)

Writing to The Straits Times, girls complained of the damage and claimed that some of them were injured as a result of the firecrackers.[4] Moreover, the girls reported that they were unable to retaliate because of the nationwide cracker ban that had been imposed. The president of Eusoff College Junior Common Room Committee - the representative body of the hostel - declared that they took a serious view against the boys’ actions and would not tolerate a repeated incident.[5]

When interviewed, the president of the Raffles Hall Junior Common Room Committee noted that the ‘raiders’ generally “felt sore” because they “found all the doors locked” even though the girls knew of their arrival and claimed to be prepared for their attack. While he did order the ‘raiders’ to not throw the crackers into the room, the order appeared to be unheeded as the boys “did spend more than $100 on crackers”.[6]

Additionally, the ‘Cracker War’ attracted the attention of the police. While the police did probe into the war, the acting Police Secretary, Mr Koh Lian Wah, stated that as no formal report was lodged with the police, they were unable to take action against any of the ‘raiders’.[7]

Further developments

In the aftermath of the ‘cracker war’, the Raffles hostelites wrote apology letters and sent flowers to the girls of Eusoff College. In their letters, the boys informed the girls that they were willing to pay for damage incurred.[8]

In an anonymous letter to The Straits Times, the author, claiming to be a veteran of three ‘Cracker Wars’ in the University of Singapore, applauded the girls for speaking up on what was considered as a "closed" and private matter. The author stated that by bringing the issue to the media’s attention, it helped to abolish the ‘ragging’ activities on campus as the university came under the scrutiny of the public.[9]

1965 Christmas Eve "Cracker War"

Details of incident

In the early hours of Christmas Eve, the boys from Dunearn Road Hostel and Raffles Hall launched a ‘Cracker War’ against the girls of Eusoff College. The three-hour assault appeared to be in defiance of a stern warning issued after last year’s incident on New Year’s Eve.[10]

The girls of Eusoff splashed soapy water down the corridors and staircases in an attempt to slow down the incoming invaders. Doors were locked and barricaded, windows shut tight and all ventilators sealed with cardboard or paper. Armed with firecrackers and cigarette lighters, the boys converged on Eusoff College after 10 pm and fired the first round of firecrackers just after midnight. As the war began in earnest, this attracted the attention of Miss Jean M. Robertson, the principal of Eusoff College and a police patrol car. However, nothing much could be done against the boys. The ‘Cracker War’ finally came to an end after 3 am.[11]

Responses (Junior Common Room Committees & police)

Where the police authorities were concerned, no offences were committed during the ‘Cracker War’. The ban on the firing of crackers had been momentarily lifted and the incident occurred on private property.[12] Moreover, there was no ‘mischief’ within the legal meaning of the term and no fire broke out on the property. However, the incident attracted the media’s attention which placed considerable pressure on the University of Singapore’s authorities to take action.

In response, the vice-president of Raffles Junior Common Room Committee claimed that no one from his hostel was involved as ‘raiders’ and those present were only spectators.[13] He further asserted that the committee decided to discontinue the ‘Cracker Wars’ a month ago, a move that was supported by a majority of the Raffles hostelites. Similarly, the president of the Dunearn Road Hostel Committee stated that their residents did not form a majority of the ‘raiders’ and had since met to impose a ban on the ‘Cracker Wars’.[14] On the other hand, the president of Eusoff Hall Committee declined to comment.

Further developments

Accepting collective responsibility, the 160 students of Dunearn Road Hostel - regardless of their participation - decided to pay a fine of $5 each following their assault on Eusoff College.[15] Furthermore, they gave an undertaking to the Vice-Chancellor, Professor Lim Tay Boh, promising that there would not be any recurrences of the 'Cracker Wars'. While the various university authorities declined to comment, a hostelite responded that by claiming collective responsibility, they hoped that the Vice-Chancellor would be prepared to end the matter there.[16]

References / Citations

- ↑ Teresa Ooi. “The Spirit of Dunearn still lives”. New Nation. August 25, 1981. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ "Still jiving, after all these years". The Straits Times. August 9, 2008. Accessed on 19 July 2019. Retrieved from: http://newshub.nus.edu.sg/news/0808/PDF/JIVING-st-9Aug-pB6.pdf

- ↑ “Row Over Cracker Raid”. The Straits Times. January 12, 1965. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Row Over Cracker Raid”. The Straits Times. January 12, 1965. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Row Over Cracker Raid”. The Straits Times. January 12, 1965. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Row Over Cracker Raid”. The Straits Times. January 12, 1965. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Police probe into university cracker raid”. The Straits Times. January 13, 1965. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Row Over Cracker Raid”. The Straits Times. January 12, 1965. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cracker war”. The Straits Times. January 15, 1965. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG

- ↑ “Cracker war raid on girls’ hostel”. The Straits Times. January 2, 1966. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cracker war raid on girls’ hostel”. The Straits Times. January 2, 1966. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cracker war raid on girls’ hostel”. The Straits Times. January 2, 1966. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cracker war raid on girls’ hostel”. The Straits Times. January 2, 1966. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cracker war raid on girls’ hostel”. The Straits Times. January 2, 1966. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cracker raid commandos pay $5 fine”. The Straits Times. January 16, 1966. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Cracker raid commandos pay $5 fine”. The Straits Times. January 16, 1966. Accessed 22 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.