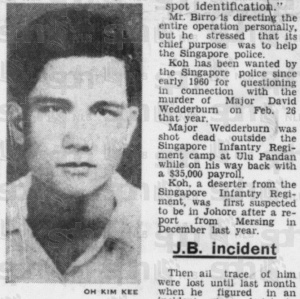

Oh Kim Kee: Serial kidnapping cases (1959 - 1960)

For 10 months between late 1959 and 1960, a series of wealthy tycoons were abducted in Singapore and Johor Bahru. The group behind the kidnappings was led by Oh Kim Kee and comprised of four to five members. Besides kidnapping millionaires, Oh and his gang were also involved in two murders. Particularly, Oh gained notoriety for repeatedly eluding the police. On 23 August 1960, Oh Kim Kee died in a gun shootout with the police.

Criminal background

In a 1975 newspaper article, Oh Kim Kee - who was also known as Singapore Public Enemy No. 1 - was described as a “meticulous planner shrouding all his moves in utmost secrecy”. His residential address was kept a secret from his gang members. As the mastermind of his operations, Oh only revealed his plans to his gang when he had to brief them. He was reported as a man who “never made mistakes” and “stressed planning and secrecy” in all his operations. He demanded perfection from his members but earned their loyalty by helping them in their difficulties.[1]

In 1953, Oh was sentenced to eight years imprisonment for robbing a cigarette van. During his stay in Changi Prison, Oh met Koh Beng Seah who would later become his second-in-command. Oh was released in 1959 after remission of his sentence for good behaviour. Following his early release, he organised a series of kidnappings that led to his involvement in two murders in 1960.[2]

Successful escapes

Based on an observer’s story from 1970, the police came close to arresting him twice. Oh's first escape happened during a police raid of his home in Kranji. Oh reportedly anticipated the raid. He had strategically positioned "portable fences" in his home to slow down the police. Before the police could clear the third row of fences, Oh had run out the back door and disappeared. In the second case, Oh managed to escape a group of detectives in Johor Bahru by diving into the Straits. He then swam to a speedboat, boarded it and raced off to a nearby island.[3]

Kidnapped victims

While it was reported that Oh pulled off a total of 12 kidnappings in 10 months, a coroner’s inquiry and various newspaper reports linked him to around five kidnapping operations and two murders.[4][5]

Tan Ling Heong (30 December 1959 - 11 January 1960)

On 30 December 1959, Tan Ling Heong, a Managing Director of a building construction firm, was abducted at the junction of Woodlands Road and Mandai Road while he was driving home with his son. According to the news reports, Tan was driving along when a black car suddenly came out into the middle of the road and blocked him. Following that, four men armed with guns and daggers jumped into Tan’s car. They forced his son to lie down on the floor while Tan was made to drive to a rubber estate at the 15th mile, Mandai Road. Tan was then bundled and ushered into another car while his son was dropped off at the main road and told to go home.[6][7]

Tan reportedly had blinding ointment rubbed into his eyes following his capture. For the next 12 days in captivity, he recounted how he lived in “total darkness”. Tied to a bed, Tan’s eyes were “plastered” and his ears “were plugged with cotton wool”. He was not allowed to speak and was constantly kept on a strict watch. Tan said that he was fed twice a day and given a cup of Ovaltine each morning.[8]

On 5 January 1960, spotted aircraft were used to search for Tan. The Marine Police fleet swept the Straits of Johor coastline and flushed out any known coastal hideouts. The Singapore police also offered a reward of S$10,000 for information on Tan's whereabouts.[9] The next day, it was reported that Tan’s family members received a letter from Tan, addressed to his brother.[10]

According to Tan's family members, a ransom of S$800,000 was initially requested. After a series of “hush-hush negotiations”, the kidnappers reduced the ransom to about S$100,000.[11] On 11 January, Tan was released somewhere in Yio Chu Kang.[12] He reportedly limped his way to a nearby petrol kiosk to telephone his mother. While the kidnappers emptied his wallet, they gave him S$5 for a taxi fare.[13]

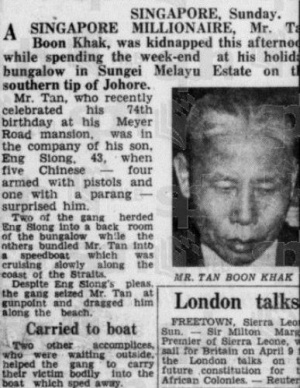

Tan Boon Khak (21 March 1960 - 28 March 1960)

On 21 March, Tan Boon Khak, a wealthy rubber magnate and the brother of multi-millionaire, Tan Lark Sye, was kidnapped while spending his weekend in Sungei Melayu Estate on the southern tip of Johor. Tan Lark Sye was the Chairman of Asia Life and Accident Assurance Society Ltd, as well as the Chairman of the Hokkien Huay Kuan and the Tan Clan Ancestral Temple.[14]

A group of five Chinese men - four armed with pistols and one with a parang - surprised Tan Boon Khak in his holiday bungalow. The men bandaged his eyes and bundled him off into a speedboat as they made their way towards the Johor Straits. Although the boat was found abandoned at Kranji, the police suspected that it was a red herring to divert their attention.[15]

On 23 March, it was reported that the kidnappers had contacted Tan’s family through telephone and a letter written by Tan.[16] The kidnappers demanded S$1 million as ransom but after multiple negotiations, accepted S$200,000 from Tan’s family.[17]

On 28 March, Tan was released after 7 days in captivity. The gang dropped Tan off at 2 AM in the jungle off Mawai Road with nothing but a blanket. At dawn, Tan found the main road and boarded a bus heading towards Kota Tinggi. Tan made it safely to a close friend’s home.[18]

Ong Cheng Siang (27 April 1960 - 6 May 1960)

On 27 April, Ong Cheng Siang, Chairman of the Green Bus Company, was kidnapped after a dinner at the Great World Amusement Park. It was reported that Ong was last seen driving home before he vanished. On 1 May, a ransom demand arrived in the form of a letter. The kidnappers demanded around S$500,000 and disclosed the location of Ong’s car.[19]

While not much was reported on his kidnapping, Ong was released on 6 May after being kept for 9 days in an underground cell. No police report was made until after his release. There were also no details regarding the ransom paid by his family.[20]

How Cheow Chye (10 August 1960 - 22 August 1960)

On 10 August, Ho Cheow Chye, a rubber merchant, was kidnapped on the Kota Tinggi - Mawai link road outside his 14-acre rubber estate at Batu Tiga, Johore. Just a few days before, Ho confessed to his close relatives that he had been shadowed several times while he was in Singapore. According to the rubber estate workers who witnessed the kidnapping, three men dragged Ho into their car while the fourth waited behind the wheel. The workers immediately called the police who then set up roadblocks within 15 minutes.[21]

Ho was released on 22 August, after 12 days in captivity. He was dropped off along Scudai Road, 20 miles away from Johor Bahru, while still blindfolded. A European planter gave him a lift to Kota Tinggi where Ho then took a bus to Rochor Road in Singapore. Once in Singapore, he took a taxi to a relative’s house in Katong. According to Ho, the kidnappers had kept him under surveillance for 4 months before kidnapping him. Ho noted that he was provided with “good food” by the kidnappers.[22] It was disclosed that Ho’s wife paid a ransom of S$60,000 for his release.[23]

Lee Chwee Kuan (August 1960)

Sometime in August 1960, Lee Chwee Kuan, a Director of a family business, was kidnapped by Oh's gang. Unlike the other victims, Lee did not make a police report about his abduction. According to Lee, he was held for 3 days and was made to pay S$90,000 along with his gold watch to secure his release. Lee confessed that the gang made death threats to his daughter, warning her of the consequences should the matter be reported to the police.[24]

Murdered victims

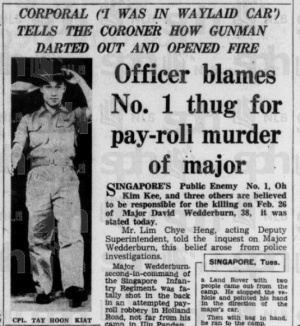

Major D.M.A Wedderburn (26 February 1960)

On 26 February 1960, Major Wedderburn, the second-in-command of the Singapore Infantry Regiment, was gunned down during an attempted pay-roll robbery.[25]

Based on the key witness’ (Corporal Tay Hoon Kiat) statement, Major Wedderburn was driving back to camp on Ulu Pandan Road after withdrawing S$35,000 from a bank for the troops’ fortnightly pay. They were ambushed when a car crossed their path and stopped a short distance away.

Two men alighted from the car and approached their vehicle. Upon realising that one of the men was holding a revolver, Major Wedderburn attempted to drive away but was shot by the gunman. Although he was wounded, the Major continued to drive towards the camp until he lost consciousness. Corporal Tay, who was in the passenger seat, took the money and ran to the safety of the camp.[26]

In their investigation, the police offered a S$5,000 reward to anyone who could provide information on the people responsible for Major Wedderburn's death.[27] They believed that Oh and his gang were responsible for the murder.[28]

Wong Siong Yin (25 July 1960)

On 25 July 1960, Oh tried to kidnap Wong Yook Kee, a watch dealer, as he was driving home with his son at the junction of Goodman Road and Wilkinson Road. The older Wong was able to escape, allowing him to call the police. In retaliation, the kidnappers "mauled" his son, Wong Siong Yin, who died without regaining consciousness 10 days later.[29]

Oh Kim Kee's death

Raid and shoot-out at 134-B Sims Avenue

On 23 August 1960, the police officers at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) received a tip-off from an informer regarding Oh’s whereabouts. That same night, the CID arranged a raid at 134-B Sims Avenue to arrest Oh and fellow gang member Yang Nan Yang.[30]

The police were divided into four teams led by: Superintendent Ong Kiang Tiong, Deputy Superintendent V. N. Ratna Singam, Deputy Superintendent Lim Chye Heng and Inspector M. Nadarajah. The teams - which comprised of a total of 12 officers - surrounded the flat and began the siege at 1.20 am. In a detailed coroner’s inquiry, the police recounted the events of the night that led to the arrest of Yang Nan Yang and the death of Oh Kim Kee.[31]

Based on their statements, Oh was crouched in the dark and waiting for them with a gun in each hand. He fired two shots at Supt. Ong before retreating into his room. After using tear gas bombs to flush other inhabitants out of the flat, the police concentrated their fire on the room occupied by Oh until they heard groans coming from inside. They found Oh, who was still armed, lying unconscious under a bed. He was eventually taken away by an ambulance but died on the way to the hospital.[32]

Further developments: Autopsy report and criminal evidence

According to the autopsy report, Dr D. Wadhwani, assistant pathologist at the Singapore General Hospital, extracted three bullets from Oh’s body. There were a total of six bullet wounds. One of the bullets was extracted from his left thigh, another from the right leg and the third from his abdomen. Dr Wadhwani also noted that most of Oh’s wounds were frontal and were not inflicted from the back, nor were they self-inflicted.[33]

After seizing the flat, the police recovered a few items that tied Oh to the series of abductions in 1960. Some of the items include: Lee Chwee Kuan’s gold watch and cash that had the same serial numbers as the ones given as ransom money in Tan Ling Heong and Ho Cheow Chye’s abduction.[34] Following the success of the shootout, Supt. Ong and Deputy Supt. Ratna were awarded the first-ever Conspicuous Gallantry Medals on 17 September 1960.[35]

Conclusion

(Johnny) Yang Nan Yang

Yang Nan Yang, also known as Johnny Yang, was detained by the police after he surrendered during the shootout. He admitted that he was paid a total of S$65,000 after kidnapping two victims, but denied his involvement in other kidnapping operations.[36] He was later banished to China but managed to escape when the ship “Santhia” made port at Hong Kong.[37]

Winnie Mok

Winnie Mok, a former cabaret girl and “trusted driver of Oh’s flashy cars” was detained under the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Ordinance. She was arrested in September 1960 when she attended the coroner’s inquiry and requested to talk to her brother, Johnny Yang Nan Yang. Mok served a year’s detention at Outram Road prison.[38]

Koh Beng Seah

Also known as “Oh Kim Kee’s No. 2”, Koh had been wanted by the Singapore police since early 1960 in connection with the murder of Major Wedderburn. After Oh’s death, Koh went into hiding in Johor. On 28 February 1962, the entire police force of Johor was mobilised to track Koh down. Wanted notices were issued to all police stations in Johor, bearing a full description of Koh who was known to have dressed as a woman to evade the police.[39]

On 3 March 1962, Koh surrendered himself to the CID in Robinson Road, accompanied by lawyer Mr David Marshall.[40] He was detained under the Criminal Law (Temporal Provisions) Ordinance and served time in Changi Prison.[41]

References / Citations

- ↑ Pakir Singh. “They’ll never catch me alive: Kim Kee”. New Nation. May 6, 1975. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Pakir Singh. “They’ll never catch me alive: Kim Kee”. New Nation. May 6, 1975. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Pakir Singh. “They’ll never catch me alive: Kim Kee”. New Nation. May 6, 1975. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Sheng Siong kidnap: Kidnappings common in the past; stories from the archives”. The Straits Times. January 9, 2014. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from: https://straitstimes.com/singapore/sheng-siong-kidnap-kidnappings-common-in-the-past-stories-from-the-archives

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Mr Tan’s 12 days of darkness”. The Straits Times. January 15, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Kidnap air hunt”. The Straits Times. January 5, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Mr Tan’s 12 days of darkness”. The Straits Times. January 15, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Kidnap air hunt”. The Straits Times. January 5, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Kidnap; Family receives 2 letters”. The Singapore Free Press. January 6, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Towkay is released”. The Singapore Free Press. January 12, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Towkay is released”. The Singapore Free Press. January 12, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Mr Tan’s 12 days of darkness”. The Straits Times. January 15, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Five thugs kidnap Lark Sye’s brother”. The Straits Times. March 21, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Five thugs kidnap Lark Sye’s brother”. The Straits Times. March 21, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Mr Tan writes to family”. The Straits Times. March 23, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Mr Tan Freed - bound and gagged for seven days”. The Straits Times. March 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Mr Tan Freed - bound and gagged for seven days”. The Straits Times. March 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Towkay’s kidnap: $500,000 ransom demand”. The Straits Times. May 1, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Bus millionaire freed by gang: Big ransom paid”. The Straits Times. May 9, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Towkay abducted after inspecting rubber estate”. The Straits Times. August 12, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Kidnap towkay freed by gang”. The Straits Times. August 23, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Murder hunt men find two guns”. The Straits Times. February 29, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Corporal ( “I was in waylaid car”) tells the coroner how gunman darted out and opened fire”. The Straits Times. October 5, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Major’s murder: $5,000 for information”. The Singapore Free Press. April 23, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Corporal ( “I was in waylaid car”) tells the coroner how gunman darted out and opened fire”. The Straits Times. October 5, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Oxygen tent for kidnap bid man”. The Straits Times. July 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Police Week will focus on heroes past and present”. The Straits Times. June 2, 1989. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Death of a Desperado”. The Straits Times. September 28, 1960. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Peries, Bob. “Kidnap thug’s girl is out of jail”. The Straits Times. August 19, 1962. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Peries, Bob. “Kidnap thug’s girl is out of jail”. The Straits Times. August 19, 1962. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Manhunt in Johore”. The Straits Times. February 28, 1962. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Wanted man gives up”. The Straits Times. March 3, 1962. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Order to detain man signed”. The Straits Times. March 20, 1962. Accessed 8 August 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.