Moonshine operations in Singapore (1930 - 1980s)

Moonshine refers to the illegal distillation of alcohol in makeshift distilleries. From the 1930s, Singapore experienced an increase in the illicit brewing of samsu - a type of spirit - in jungles and rural areas. To combat this, the Singapore Customs Department conducted intensive raids against these moonshiners. Operations occurred between dusk and dawn. Moonshiners preferred to work in cooler conditions, while the dark allowed them a better chance of escaping a raid.[1] Eventually, moonshine activities declined in the late 1980s, although sporadic cases were reported in the newspapers in later years.

Illicit samsu

Origins

Illicit samsu was known as sua pah chiew (bukit samsu) by the Chinese and lallang thani (grass water) by the Tamils.[2] It was often regarded as a “poor man’s drink” because of its cheap price. Moreover, it was mainly used by the Chinese as an ointment and as an offering during prayers.[3] The brewing of illicit samsu was first reported in 1930. Two Chinese men, a father and son team, were charged under the Liquor Ordinance and fined $1,150.[4]

By the 1960s, there were a total of three licensed samsu distilleries in Singapore. Opened in 1934, Tay Miang Huat Distillery at Alexandra Road was the oldest of the three.[5] In 1947, Lian Hup Distillery at Kampong Ampat was established.[6][7] Finally, in 1961, Singamas Chemical Industries Ltd. opened at Little Road.[8] Despite the availability of legal samsu, illicit samsu continued to be patronised.

Process

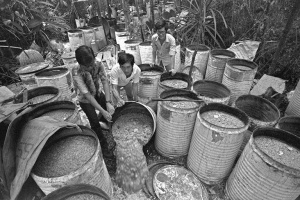

Illicit samsu was made by mixing parboiled rice, brown sugar and yeast with water to form a mash. It was then stored in containers and allowed to ferment. The fermentation process would normally take between four to six days. However, the process would take a week if the containers were buried underground. Dry weather season would also allow the mash to ferment quicker.[9]

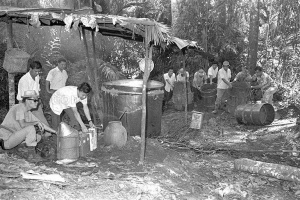

A complete distilling apparatus set consisted of a still, a condenser, a dripping pipe, a scoop, a funnel, and a receiver container for the distillate. The still was usually of zinc or aluminium material and the size commonly ranged between 80 to 100 gallons in capacity. Distillers would also use pressure stoves which helped to heat the mash quicker and minimise smoke emissions. However, the location of these distilleries was often revealed by the hissing sound emitted by the stoves or the strong and sour odour of the mash.[10]

Health risks

Drinking illicit samsu was discouraged by Customs Officers as it was prepared under unhygienic conditions. Illicit samsu contained a high level of lead that came from the utensils used in the distilling process. This could cause lead poisoning which would trigger blindness, circulatory collapse and muscular paralysis. Additionally, distillers would add a large amount of methylated spirit to dilute the samsu, which had severe effects on the health of drinkers.[11] These distillation apparatus were also often in neglected conditions; they were coated in rust or verdigris. At the same time, plastic containers, rubber tubes and jerry cans holding the distilled liquor often bore traces of toxic chemicals or acidic substances.[12]

Furthermore, the water used in the making of illicit samsu was drawn from public sources and were never chlorinated, posing additional health risks. At times, the distillation process even used stagnant, algae-covered water from a pond.[13] Moreover, the fermentation drums were usually buried near chicken coops, pigsties or bathrooms. When not properly covered, insects and rodents could find their way into the drums and remain trapped inside. Additionally, the distilleries did not have proper ventilation and sanitation.[14]

Popularity

The popularity of illicit samsu stemmed from its cheap price. A 630ml bottle of legal samsu used to cost around S$6 which was about the same price as a bottle of beer. However, illicit samsu costs around S$3 - half the price of a legal bottle. Additionally, it had a higher alcohol content than beer. It was reported that illicit samsu had a 27 to 51% alcohol content. As a comparison to other hard liquors, brandy and whisky had a 45 and 40% alcohol content respectively.[15] According to an owner of a liquor shop, “Half a bottle will make you drunk. You need six bottles of beer to do the same”.[16]

The demand for illicit samsu often increased during festive holidays, such as Chinese New Year, the Dragon Boat Festival and the Hungry Ghost Festival.[17][18] During the 1950s and 1960s, illicit samsu was popular with coolies and rickshaw pullers. In later years, the drink gained traction among foreign workers and labourers.[19]

Illegal samsu distilleries

Location

In the 1960s, the illegal distilleries were concentrated around the Seletar and Braddell Road area. The distillers used the cover of dense forest reserves to conceal their operations.[20] In the 1970s, moonshiners moved to more secluded areas such as rural districts and kampongs, especially near or behind uninhibited huts, bathrooms, chicken coops and pigsties.[21] It was reported that during raids, metal drums filled with mash were often unearthed from the jungle grounds or ingeniously hidden in the mud to avoid detection.[22]

As water was an integral ingredient in the distillation process, most makeshift distilleries were situated around streams, drains, ponds and wells. When water was not readily available, some distillers would construct an underground pipe or connect the water from the nearest well or pond to their distillery using a rubber hose. The hose would then be removed after each operation. Some would even dig wells in the jungles or forest reserves for their water supply. When not in use, these wells would then be camouflaged with planks, leaves and branches to blend in with the surroundings.[23]

In the 1980s a handful of moonshiners conducted their operations from high-rise flats in Housing Board estates and private blocks. The move was fueled by the Customs Officers’ constant raids and urban redevelopment projects.[24] In the late 1980s, some distilleries existed in the forested areas in Yio Chu Kang, Hougang, Jurong and Sembawang which were momentarily untouched by redevelopment projects.[25]

Samsu dens

Besides illegal distilleries, there were liquor parlours or dens that illegally retailed samsu from their homes. The parlours were described as “dimly-lit rooms, mostly in the back of dwelling houses”.Some of these dens were located in the city area, Tiong Bahru, Jalan Besar and Joo Chiat.[26] Serangoon Road, Tanjong Pagar and Nelson Road were some of the main areas where people were reportedly found drunk with samsu from illegal dens.[27]

Samsu syndicates

In 1966, it was reported that there were about a dozen big syndicates that operated such distilleries. Described as “ruthless and well-organised”, these syndicates operated 20 to 30 distilleries at once. In turn, they could earn well over S$5,000 to S$10,000 per month, indicating that moonshining was a lucrative business. Customs Officers reported that they used to eradicate an average of one “giant-sized” distillery each day.[28] To evade capture, members of the syndicate would blow whistles, let off firecrackers and have dogs barking whenever Custom Officers were spotted.[29]

Customs department

In 1959, it was estimated that the Customs Department lost S$1,000,000 due to the brewing of illicit samsu.[30] To combat this, the department conducted relentless raids and patrols around known samsu brewing areas. In the 1970s, illicit samsu brewing was identified as a serious problem. This led to the creation of three special Customs squad who monitored samsu brewing activities at Changi, Lim Chu Kang and Kangkar until the 1980s.[31]

When caught, an illicit samsu brewer or even an owner of a bottle could be charged with a heavy fine or jail time if he failed to pay the fine. He would also be subjected to constant surveillance by the Customs in the future.[32]

Decline

The illicit brewing of samsu gradually went into decline in the late 1980s. The intensive raids by the Customs Department led to the demise of big samsu syndicates, in turn, leading to the disbandment of the three special squads.[33] Secondly, urbanisation and redevelopment of forested areas and rural haunts exposed the makeshift distilleries. Economic inflation also caused an increase in the price of sugar and rice, the two main ingredients of samsu.[34]

In the 1980s, only a handful of moonshiners remained. They worked individually, producing small and irregular quantities that could not meet the demand of their customers. Figures show that the production of illicit samsu declined since 1978. The figures below summarise the amount of fermented mash and samsu that the Customs Department seized between 1978 and 1980.[35]

| Fermented mash (litres) | Samsu (litres) | Destroyed stills | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 61,200 | 1,518 | 39 |

| 1979 | 30,800 | 1,900 | 17 |

| 1980 | 6,000 | 1,300 | 15 |

However, sporadic cases of illegal samsu brewery were reported in later years. The last reported case of samsu brewing was reported in 2001 when an alcohol-distilling shack was discovered in Seletar.[36]

References / Citations

- ↑ Ismail Kassim. “Samsu - the toast of the poor man”. New Nation. December 30, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Ismail Kassim. “Samsu - the toast of the poor man”. New Nation. December 30, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Leong Chan Teik. “Illegal distillery for samsu smashed”. The Straits Times. June 7, 1989. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ "“Bootleg” liquor”. The Straits Times. December 23, 1930. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Saraswathi Sundram. “Local distillery selling samsu through supermarket chain”. The Straits Times. February 21, 1989. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Liquor range is extended”. The Straits Times. November 27, 1989. Accessed 31 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Campbell, William. “Trailing the illicit samsu vendors”. The Straits Times. August 26, 1973. Accessed 31 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Success story of small local industry”. TheStraits Times. October 15, 1966. Accessed 31 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Ismail Kassim. “Samsu - the toast of the poor man”. New Nation. December 30, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chan, Douglas. “Diehard samsu operators using new tactics to survive”. New Nation. December 31, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chua Chin Chye. “Samsu still flows freely here”. New Paper. November 24, 1988. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chan, Douglas. “Diehard samsu operators using new tactics to survive”. New Nation. December 31, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Leong Chan Teik. “Illegal distillery for samsu smashed”. The Straits Times. June 7, 1989. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chan, Douglas. “Diehard samsu operators using new tactics to survive”. New Nation. December 31, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “The 3-D Connection”. New Nation. August 17, 1975. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chua Chin Chye. “Samsu still flows freely here”. New Paper. November 24, 1988. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Customs seize mash in 2 raids”. The Straits Times. February 7, 1964. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Leong Chan Teik. “Illegal distillery for samsu smashed”. The Straits Times. June 7, 1989. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chua Chin Chye. “Samsu still flows freely here”. New Paper. November 24, 1988. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “‘Moonshine men’ busier, too”. The Straits Times. May 11, 1954. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Ismail Kassim. “Samsu - the toast of the poor man”. New Nation. December 30, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Samsu in the Kallang Basin”. The Straits Times. April 19, 1963. Accessed 31 July. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Ismail Kassim. “Samsu - the toast of the poor man”. New Nation. December 30, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ K. S. Sidhu. “Moonshiners move their stills into high-rise flats”. The Straits Times. September 3, 1980. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chua Chin Chye. “Samsu still flows freely here”. New Paper. November 24, 1988. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “12 held in raids on liquor parlours”. The Straits Times. October 19, 1962. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Illicit liquor - a thorn in side of Customs”. The Straits Times. January 13, 1963. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ N. G. Kutty. “Illicit brewery gangs crippled by raids”. The Straits Times. November 8, 1976. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “‘Moonshine men’ busier, too”. The Straits Times. May 11, 1954. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Mash seized in a samsu swoop”. The Straits Times. July 6, 1960. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chua Chin Chye. “Samsu still flows freely here”. New Paper. November 24, 1988. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chan, Douglas. “Diehard samsu operators using new tactics to survive”. New Nation. December 31, 1974. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Chan, Douglas. “So good that they lost their jobs”. New Nation. May 1, 1980. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ N. G. Kutty. “Illicit brewery gangs crippled by raids”. The Straits Times. November 8, 1976. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ K. S. Sidhu. “Moonshiners move their stills into high-rise flats”. The Straits Times. September 3, 1980. Accessed 30 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ “Alcohol-distilling shack discovered in Seletar”. The Straits Times. February 18, 2001. Accessed 31 July 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.