Subaraj Rajathurai: Difference between revisions

Dayana Rizal (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Dayana Rizal (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| birth_date = 16 April 1963 | | birth_date = 16 April 1963 | ||

| birth_place = Kandang Kerbau (KK) Hospital, Singapore | | birth_place = Kandang Kerbau (KK) Hospital, Singapore | ||

| death_date = 22 October 2019 | | death_date = 22 October 2019 (56 years old) | ||

| education = Guillemard East Primary School, Tanjong Katong Technical School, Siglap Secondary School, Stamford College | | education = Guillemard East Primary School, Tanjong Katong Technical School, Siglap Secondary School, Stamford College | ||

| known for = Nature Tour Guide, Wildlife Consultant | | known for = Nature Tour Guide, Wildlife Consultant | ||

Revision as of 15:24, 6 November 2019

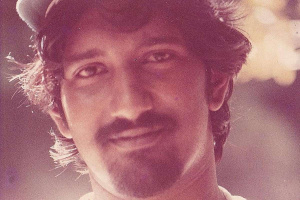

Subaraj Rajathurai was Singapore’s first licensed nature tour guide and a wildlife consultant. In 1985, Subaraj joined the Nature Society Singapore where he was an active member of the bird group.[1] By the end of 1993, he founded the Vertebrate Study Group conducting scientific research and data collection for Singapore’s National Parks Board (NParks) and the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.[2][3] Subaraj passed away in his sleep on 22 October 2019 at 56 years of age.[4]

Personal life

Subaraj was born on 16 April 1963 at Kandang Kerbau (KK) Hospital. His parents were teachers and he had an older brother and a younger sister.[5]

Education

Subaraj studied at Guillemard East Primary School and Tanjong Katong Technical School. He chose to repeat his ‘O’ levels at Siglap Secondary School before enrolling in Stamford College, a private institution for qualification to university. While at Stamford College, Subaraj walked out of a class and dropped out of college after he was tasked to dissect a frog.[6]

After two years in National Service (NS), Subaraj spent four years doing fieldwork for about five days a week. He studied Singapore’s flora and fauna by wandering around areas like Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and MacRitchie. After recording his observations, he would conduct additional research at the National Library.[7]

Besides being self-taught, Subaraj also learnt about wildlife from prominent naturalists such as Wee Yeow Chin, Dennis Murphy and Dennis Yong.[8]

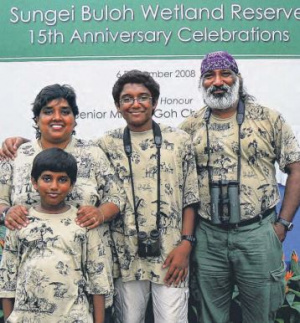

Marriage & family

Together with his wife, Shamla Jeyarajah Subaraj, Subaraj had two sons, Serin and Saker, who were named after a species of finch and falcon respectively.[9]

Serin shares his father’s interest in wildlife and co-founded the Herpetological Society of Singapore that focuses on the conservation of reptiles and amphibians.[9] As of 2019, Serin is studying wildlife conservation and marine biology at Murdoch University.[10]

Career

Apart from his professional career, Subaraj had been volunteer Nature Warden at Bukit Timah Nature Reserve for over 20 years.[11] His reputable career as a naturalist has earned him guest lecture spots at local universities for courses like environmental law, natural sciences and geography.[12]

Licensed nature tour guide (STB)

In 1990, Subaraj attained his tour guide license from the Singapore Tourism Board (STB). This license legalised his nature tours and made him Singapore’s first professional eco-tourist guide. With the license, Subaraj expanded his self-designed tour programmes from 4 to over 50 tours.[13]

The tours included birdwatching, nature walks, educational nature study programmes and special overseas nature programmes. Subaraj often offered personalised programmes tailored to his client’s requirements.[14]

Strix Wildlife Consultancy

Subaraj established Strix Wildlife Consultancy in the 2000s after recognising that developers needed a wildlife consultant for infrastructure development.[15]

According to Subaraj, the name ‘Strix’ came about after he noticed that most of his birdwatching clients came to Singapore to look specifically for the spotted wood owl. Realising the owl's rarity and popularity, Subaraj incorporated the bird into the company’s logo and named his company ‘Strix’, which is the genus name of the owl.[16]

Strix provides services like field surveys and research, wildlife filming, researching suitable routes for nature trails and also training programmes.[17] Based on his interviews, Subaraj’s clients also included several resorts in Bintan, Nikoi Island and Cempedak Island.[18]

Conservation Consultant (NParks)

When NParks was established in the 1990s, Subaraj was invited to be a Conservation Consultant on the Nature Reserves Committee. The committee had organised a complete study of all the nature reserves in Singapore, a study that had taken four years to complete. The MacRitchie Treetop Walk was one of the successful products of the committee’s work.[19]

Notable conservation efforts

As an advocate of Singapore's wildlife, Subaraj had been involved in numerous development projects where he sought to protect nature in the face of urbanisation.

Cross Island MRT line & Mandai (2018 - 2019)

At the time of his death in 2019, Subaraj had been working as a consultant for the new Cross Island MRT Line and the Mandai eco-tourism hub.[20][21] He had continuously asked for more mitigation measures to be put in place to ensure the animals’ safety and to reduce the impact of site surveys on the wildlife in the area.[22][23][24]

Following a spate of roadkill incidents in Mandai Lake Road in 2018, Subaraj had refused to sign a non-disclosure agreement with the developer of the Mandai project.[25]

Chek Jawa Wetlands (2000 - 2001)

The Chek Jawa Wetlands is located on the South-eastern tip of Pulau Ubin, one of Singapore’s offshore islands. In an interview, Subaraj recounted how Chek Jawa was introduced to the Singapore public. Subaraj recalled that they had been filming at Chek Jawa for the television programme “Secret Worlds”. In each episode of the show, Subaraj and the film crew explored Singapore's nature in undisclosed locations. During the Chek Jawa episode, Subaraj went off script and revealed their location to raise awareness that Chek Jawa was slated for reclamation.[26]

After the show had been aired on Mediacorp’s Channel U, Chek Jawa gained public interest and visitors to the area increased. As a result, the government announced that the reclamation project would be delayed for ten years. Subaraj and members of the nature community used the time to document Chek Jawa’s marine life and fuelling conservation effort. In 2019, Chek Jawa remains as a conservation site on Pulau Ubin.[27]

Lower Peirce Reservoir conservation plan (1992)

In 1992, the Nature Society received leaked information that the Public Utilities Board (PUB) wanted to construct a golf course at the Lower Peirce Reservoir. Various nature groups and the National University of Singapore (NUS) collaborated to conduct an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) by studying the flora and fauna in the area. Subaraj was the coordinator for the fauna studies in the EIA, a role that he had taken up due to his experience with wildlife in the area.[28]

The published study was for sale in bookstores across Singapore. With this unforeseen exposure, PUB shelved their plans thereby conserving more than 100 hectares of forest at the reservoir.[29]

In an interview, Subaraj mentioned that the Lower Peirce issue was serious as the individuals involved in the EIA were perceived to be “interfering with the government”. The individuals involved were subjected to checks by the Internal Security Department. As a result of his participation in the movement, Subaraj’s documentary was taken off the air and never screened on television despite earlier advertisement.[30]

Master Plan for the Conservation of Nature in Singapore (1990)

Subaraj played a role in drafting the Master Plan for the Conservation of Nature in Singapore, as part of the bird group and the consultation committee. It was a collective work between different nature groups working on different nature sites.[31] Published in 1990, the document details all the potential areas that were protected and needed to be protected, such as the Mandai mangrove and Bukit Timah Nature Reserve.[32]

Sungei Buloh (1988 - 1989)

In 1988, the government planned to develop Sungei Buloh for agrotech farming. Recognising that such development would harm the nature in the area, Subaraj and three other individuals wrote a conservation proposal for Sungei Buloh. In the proposal, they listed out the area’s potential for research, education and tourism. After eight months, they sent the proposal out to “everyone and anyone who would read it”.[33]

In 1989, the Minister for National Development, S Dhanabalan, announced on television that the government decided to conserve Sungei Buloh “for a while”, keeping the area on a 15-year lease. In 2019, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve is a permanent feature in Singapore for educating students on top of being an important area for migratory birds.[34]

Death

On 22 October 2019, Subaraj died of a heart attack during an afternoon nap. According to his wife, she had tried to rouse him for lunch only to discover that he was gone. The funeral was held the next day at his home in Tampines. Dozens of mourners from the nature community turned up in green as a symbolic gesture to recognise his dedication to nature conservation in Singapore for the past 30 years.[35][36]

References / Citations

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Low Youjin. “‘One of S’pore’s greatest nature warriors’: Subaraj remembered by many as an inspiration, voice for animals”. Today.October 23, 2019. Accessed 24 October 2019. Retrieved from todayonline.com.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Tan, Audrey. “Dozens turn up in green for wildlife consultant’s funeral”. The Straits Times. October 24, 2019. Accessed 24 October 2019. Retrieved from thestraitstimes.com.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lee, Venessa. “The Life Interview with Subaraj Rajathurai: Self-taught naturalist stumbled upon his calling”. The Straits Times. February 20, 2017. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from straitstimes.com.

- ↑ Low Youjin. “‘One of S’pore’s greatest nature warriors’: Subaraj remembered by many as an inspiration, voice for animals”. Today.October 23, 2019. Accessed 24 October 2019. Retrieved from todayonline.com.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ “Subaraj Rajathurai”. Strix Wildlife Consultancy. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from subaraj.com.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ “Subaraj Rajathurai”. Strix Wildlife Consultancy. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from subaraj.com.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Lim, Adrian. “LTA to suss out new MRT line’s green impact”. My Paper. February 25, 2014. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- ↑ Lin Yangchen. “Green tweaks for Mandai nature hub”. The Straits Times. July 27, 2016. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from straitstimes.com.

- ↑ Neo Chai Chin. “More measures to reduce impact of site surveys for Cross Island Line”. Today. June 8, 2016. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from todayonline.com.

- ↑ Toh Ee Ming. “Nature groups propose changes to alleviate environmental impact in Mandai”. Today. July 28, 2016. Accessed 24 October 2019. Retrieved from todayonline.com.

- ↑ “Cross Island Line site investigations haven’t driven away rare animals from nature reserve, says LTA”. Today. June 9, 2018. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from todayonline.com.

- ↑ Tan, Audrey. “Wildlife consultant threatens to pull out of Mandai developer talks after roadkill incidents”. The Straits Times. July 12, 2018. Accessed 29 October 2019. Retrieved from straitstimes.com.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Low Youjin. “‘One of S’pore’s greatest nature warriors’: Subaraj remembered by many as an inspiration, voice for animals”. Today.October 23, 2019. Accessed 24 October 2019. Retrieved from todayonline.co.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Subaraj Rajathurai. “Social Sector”. National Archives of Singapore. January - May 2018. Accessed 28 October 2019. Retrieved from Archives Online.

- ↑ Lim, Janice and Low Youjin. “‘Gentle giant’ and iconic conservationist Subaraj Rajathurai dies”. Today. October 22, 2019. Accessed 24 October 2019. Retrieved from todayonline.com.

- ↑ Tan, Audrey. “Dozens turn up in green for wildlife consultant’s funeral”. The Straits Times. October 24, 2019. Accessed 24 October 2019. Retrieved from thestraitstimes.com.